Returning therapy clients: Determining prevalence rates and identifying predictive variables

Staff who work in college counseling centers are aware that many clients discontinue services only to return to treatment at a later time. Thus, a longstanding question within the field of collegiate mental health is how often do clients return for subsequent courses of services and are there signs or predictors that might signal if a client is more likely to return to services. To examine this further at CCMH, Kilcullen et al. (2020) evaluated the rates at which clients return for additional courses of therapy in university counseling center (UCC) settings and a range of associated variables.

CCMH data from 2013 to 2017 were used for this study, which resulted in a sample of 8,329 clients from 52 different counseling centers, after stringent inclusionary criteria were applied and narrowed the pool. These criteria required that clients attend two or more appointments during their first course of therapy as well as provide relevant data on Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms (CCAPS) and Standardized Data Set (SDS) variables, some of which were more infrequently used. An additional course of therapy was operationally defined as attending at least 1 individual or group therapy session 90 days after the end of a previous course of services at the counseling center.

How often do clients return to treatment?

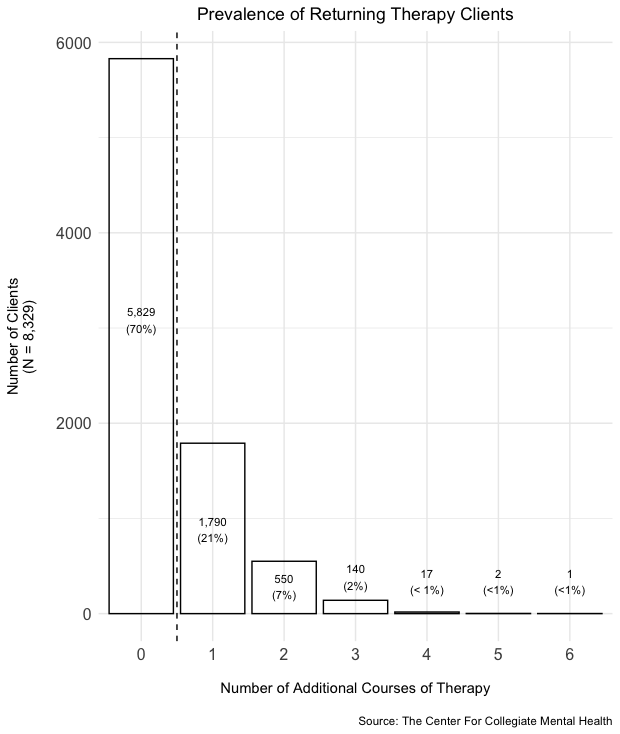

Results demonstrated that 2,500 clients (30%) returned for at least one additional course of therapy. As shown in the figure below, the majority of therapy returners came back for only one additional course of therapy (N = 1,790). Among the 2,500 returning therapy clients, clients attended an average of about 9 sessions during their initial course of therapy compared to 7 appointments in their second course treatment.

What factors predict return to treatment?

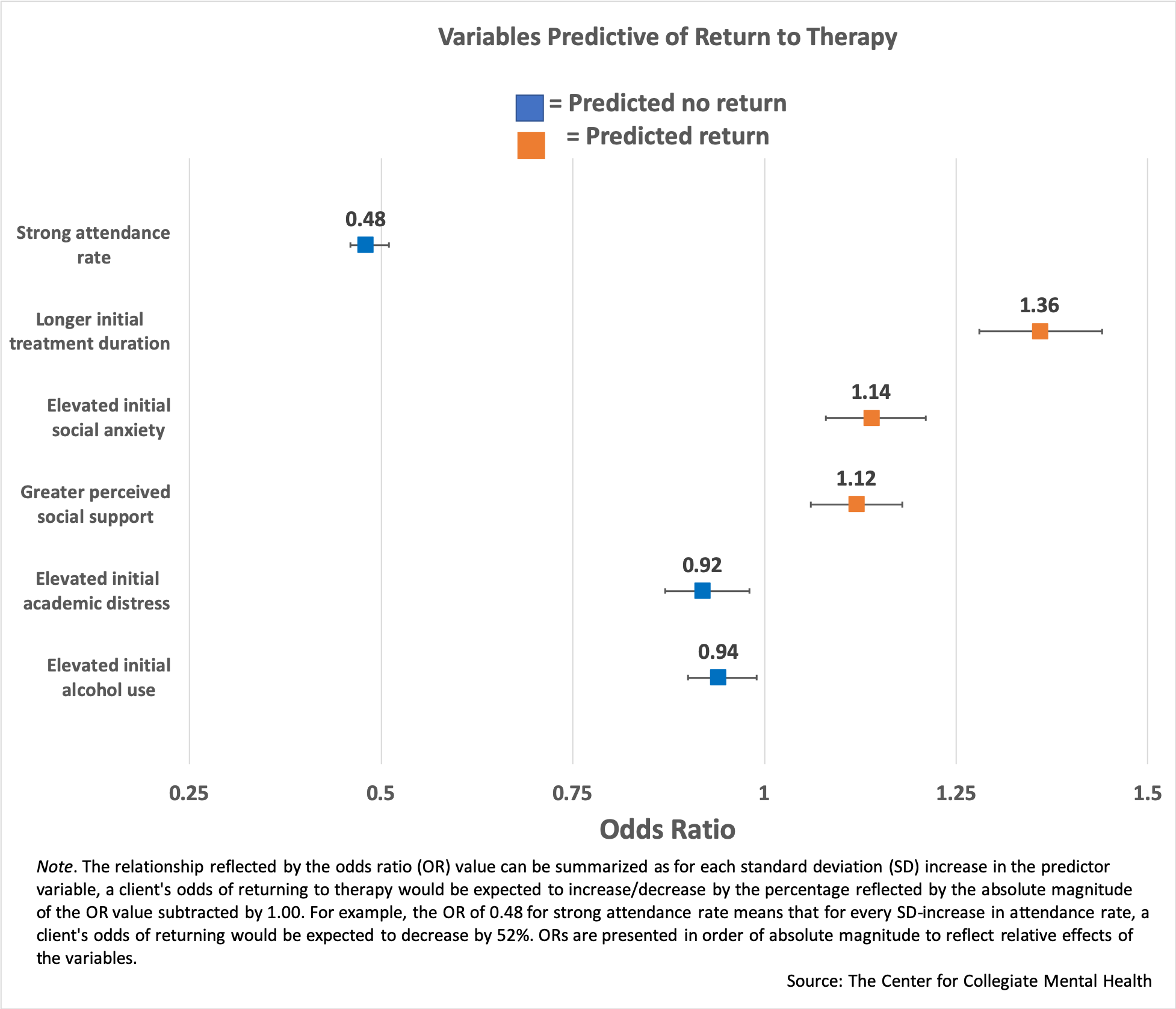

As shown in the figure below, a total of 6 variables were identified that predicted whether a client would return to services.

The following variables increased the likelihood that a client would return to therapy:

- Clients with longer initial treatment durations (i.e. more attended appointments).

- Elevated social anxiety during the first course of therapy.

- Greater perceived levels of social support.

The following variables decreased the likelihood that a client would return to treatment:

- Clients with well above average (i.e. greater than 1 standard deviation above the mean) attendance rates during their initial course of treatment.

- Elevated academic distress during the first course of therapy.

- Elevated alcohol use during the initial course of treatment.

Measures of initial-course baseline symptomatology were derived from clients’ first completed administration of the CCAPS, perceived social support was measured via the accompanying item on the SDS, and attendance rate and initial treatment duration were derived from appointment data included in the CCMH data.

Suggested reasons why clients may return to therapy

Understanding why UCC clients may or may not return to therapy (and why some variables may increase or decrease the likelihood of return to therapy) requires acknowledging the challenges faced by college students and treatment limitations experienced by many UCCs. This perspective guided the following take-aways from the present study:

- The finding that elevated alcohol use and academic distress are associated with a decreased likelihood of returning to therapy might suggest these concerns were successfully treated during the initial course of therapy or perhaps these concerns were temporary in nature. Indeed, UCC clinicians have been shown to be particularly adept at treating academic distress (Lockard et al., 2012), and there are widely used effective abbreviated interventions to address alcohol-related issues, such as the Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS, Dimeff et al., 1999).

- Social anxiety may be persistent and difficult to treat, as increased levels of symptoms at baseline was associated with increases in likelihood of returning to therapy. One possibility is while many clients with high levels of social anxiety benefitted from treatment, perhaps they could benefit from additional treatment.

- Clients with stronger perceived social support were found to be more likely to return to therapy. While one might expect decreased levels of perceived social support to be associated with greater distress or the need for additional treatment, it may be students with a strong social support appreciate the value of interpersonal connections and view therapy as an opportunity for an additional intimate relationship. Alternatively, it may be people who provide social support encourage greater self-awareness or even help-seeking behavior.

- Client’s initial treatment duration increased the likelihood of returning to therapy where longer treatments (i.e., more attended sessions) were associated with return to therapy. It is possible that clients with longer courses of initial therapy may have prematurely ended services due to the common short-term treatment model in UCCs. That is, clients who did not receive enough initial treatment may have returned to therapy to complete treatment, while, on the other hand, clients who remained in services until they achieved their therapy goals are less likely to return.

- Poorer attendance rates were strongly associated with increased likelihood of returning to therapy. Considering the dose effect observed in naturalistic settings (i.e., that more therapeutic change is associated with increased number of sessions), this finding may indicate that some clients feel they need to return to therapy because they have not resolved their problems and want to make up for the inadequate dose of therapy received during their initial treatment courses. It is also important to consider that poor attendance may be a symptom (i.e., a client characteristic) and part of a client’s clinical presentation.

Implications for counseling center staff

Approximately 30% of clients who seek treatment at UCCs return to therapy after an initial course of treatment. Regarding the symptom-specific findings (i.e., pertaining to alcohol use, academic distress, social support, and social anxiety), it is important to acknowledge that it cannot be determined exactly why these variables were associated with increased/decreased likelihoods of returning to services. Nevertheless, the relationships between these variables and return to therapy highlights the importance for clinicians to be mindful of these variables and conduct comprehensive, holistic evaluations of their clients when forming case conceptualizations.

For UCC staff and administrators, the current findings suggest that both inconsistent attendance and longer treatment lead to increased consumption of services overall, which have implications for center practices, such as session limits and attendance policies. Indeed, a previous CCMH Annual Report highlighted that arbitrary treatment limits can be problematic; it is important to be mindful that clients change at different paces and arbitrary treatment limits can blunt the impact of services that may have otherwise achieved change for students in treatment. Such clients may benefit from flexible session limits based on need, and UCCs may gain from a cost-benefit perspective as these clients may utilize less resources in the long-term. Beyond such policy considerations, these findings also might be a reflection of the simple reality that many clients need more treatment to avoid relapses and follow-up care down the road. Finally, both UCC clients and clinicians may benefit from acknowledging that clients are more likely to return to care if attendance is inconsistent. Addressing attendance early and consistently in treatment seems important to improve the efficiency and duration of the client’s care. If this is done systematically within a center, it may then improve both overall treatment outcomes and the efficiency of services offered.

Ultimately, more research will be needed to inform these policies and recommendations. A better understanding of the variables associated with a return to services could help inform UCC policies and procedures, which might allow clients to maximize the effectiveness of their initial treatment experience and reduce the likelihood of unmet need and increased service consumption in the future.